THE FESTIVAL OF SHEIK ADI IN LALISH, THE HOLY VALLEY OF THE YEZIDIS

Eszter Spat

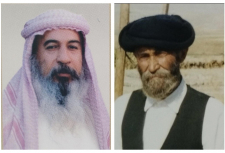

A. Henry Layard (1817–1894), English diplomat and archaeologist, visited the festival over 150 years ago, the number of pilgrims was around 5000. Today this number seems to have swollen to an immeasurable extent; it seemed that throughout the week an ever-increasing crowd kept arriving, while none of them left. There were even Yezidis from Syria. The majority came from over the border, that is from Sheikhan in what used to be Saddam Hussein’s Iraq, and some even more excitingly from the Jebel Sinjar, a mountain in the Syrian plain, traditionally isolated from external influences and for over a hundred years a stronghold and refuge of Yezidis. Most of the people coming from Sinjar still wear their traditional dress; the men wear Arab style headgear and long robes, with the capes of the rich or important embroidered in gold on the edges. Some of the Sinjaris of a more conservative turn of mind even have long plaited hair hanging down at their temples, as described by travelers in the early nineteenth century, not to mention the obligatory mustaches of the Yezidis that reach aweinspiring proportions among Sinjaris. All these people arrived carrying food for days, mattresses, blankets, cooking pots, and sometimes even tents, although more often the manycoloured patchwork sheets pilgrims bundle their things into when carrying them on their heads are later used as a kind of tent, erected over four poles. By the end of the week such colourful “tents” were set up even on the roof of the sanctuary guesthouse, that is, the house of the leading faqir, who takes care of the sanctuary throughout the year. Whole families were living, sleeping, cooking, and eating under the protection of such tents. The families camping out in such a nomadic style belonged to the most noble lineages. Each ojax, or family line, has its own allocated place to camp in Lalish, the precincts of the sanctuary complex being reserved for the most important members of the community. Since the main diet is goat meat, many of these long-robed “Arabs” arrived tugging an unfortunate, reluctant goat or two on the end of a rope. As the consumption of meat was high in the guesthouse, where entertaining the noble guest is the sacred duty of the faqir in charge of the sanctuary, one side of the sanctuary soon became slippery with the blood of the victims, who were killed and cut up in front of the stairs leading to the rooms of the prince. However, not much of this fervent activity could be seen or guessed on the first night: Lalish was still peaceful and clean. Hygiene is one of the major flaws of this feast.

There is no sewerage in Lalish. Water for drinking, cooking, and washing is carried in containers from the Sacred White Spring—surrounded by a jostling crowd all day long—and dirty water is splashed on the ground. I was taken to the main hall of the guesthouse adjoining the sanctuary, and invited to sit in the part reserved for men, a many-columned long hall with one side open to the courtyard. This was a great honor, for women invariably sit in their own section—though men can and do come visiting there. After having consumed some boiled goat-meat, boiled chicken and rice (the staple food for the week) for dinner, we went to witness the Sema Evari or the evening dance of the religious men, accompanied by the music of three kewels, sacred singers. Twelve men dressed in white walked in pairs with curious, ceremoniously choreographed steps following an old faqir, who was wearing a sooty black, long fur cape and hat (allegedly the one worn by Sheikh Adi). While the kewels played their plaintive tunes, the dancers slowly circled around the holy fire lit in the middle, said to symbolize both the Sun and the Godhead. Outside the circle stood a faqra (Yezidi nun) holding a small pail with what looked like smoking coals.

Tags:

THE FESTIVAL OF SHEIK ADI IN LALISH, THE HOLY VALLEY OF THE YEZIDIS

Eszter Spat

A. Henry Layard (1817–1894), English diplomat and archaeologist, visited the festival over 150 years ago, the number of pilgrims was around 5000. Today this number seems to have swollen to an immeasurable extent; it seemed that throughout the week an ever-increasing crowd kept arriving, while none of them left. There were even Yezidis from Syria. The majority came from over the border, that is from Sheikhan in what used to be Saddam Hussein’s Iraq, and some even more excitingly from the Jebel Sinjar, a mountain in the Syrian plain, traditionally isolated from external influences and for over a hundred years a stronghold and refuge of Yezidis. Most of the people coming from Sinjar still wear their traditional dress; the men wear Arab style headgear and long robes, with the capes of the rich or important embroidered in gold on the edges. Some of the Sinjaris of a more conservative turn of mind even have long plaited hair hanging down at their temples, as described by travelers in the early nineteenth century, not to mention the obligatory mustaches of the Yezidis that reach aweinspiring proportions among Sinjaris. All these people arrived carrying food for days, mattresses, blankets, cooking pots, and sometimes even tents, although more often the manycoloured patchwork sheets pilgrims bundle their things into when carrying them on their heads are later used as a kind of tent, erected over four poles. By the end of the week such colourful “tents” were set up even on the roof of the sanctuary guesthouse, that is, the house of the leading faqir, who takes care of the sanctuary throughout the year. Whole families were living, sleeping, cooking, and eating under the protection of such tents. The families camping out in such a nomadic style belonged to the most noble lineages. Each ojax, or family line, has its own allocated place to camp in Lalish, the precincts of the sanctuary complex being reserved for the most important members of the community. Since the main diet is goat meat, many of these long-robed “Arabs” arrived tugging an unfortunate, reluctant goat or two on the end of a rope. As the consumption of meat was high in the guesthouse, where entertaining the noble guest is the sacred duty of the faqir in charge of the sanctuary, one side of the sanctuary soon became slippery with the blood of the victims, who were killed and cut up in front of the stairs leading to the rooms of the prince. However, not much of this fervent activity could be seen or guessed on the first night: Lalish was still peaceful and clean. Hygiene is one of the major flaws of this feast.

There is no sewerage in Lalish. Water for drinking, cooking, and washing is carried in containers from the Sacred White Spring—surrounded by a jostling crowd all day long—and dirty water is splashed on the ground. I was taken to the main hall of the guesthouse adjoining the sanctuary, and invited to sit in the part reserved for men, a many-columned long hall with one side open to the courtyard. This was a great honor, for women invariably sit in their own section—though men can and do come visiting there. After having consumed some boiled goat-meat, boiled chicken and rice (the staple food for the week) for dinner, we went to witness the Sema Evari or the evening dance of the religious men, accompanied by the music of three kewels, sacred singers. Twelve men dressed in white walked in pairs with curious, ceremoniously choreographed steps following an old faqir, who was wearing a sooty black, long fur cape and hat (allegedly the one worn by Sheikh Adi). While the kewels played their plaintive tunes, the dancers slowly circled around the holy fire lit in the middle, said to symbolize both the Sun and the Godhead. Outside the circle stood a faqra (Yezidi nun) holding a small pail with what looked like smoking coals.

Tags: